ARTICLE: What does it take to be a data activist?

Introduction

In 2022, I started working on a project called “From Data Literacy to Data Activism” within the Landecker Democracy Fellowship[1], which emerged from a series of critical observations I made in my dual role as a researcher and teacher, but also from social and technological phenomena that have recently gained a lot of attention. First, the European Commission points to the digital transformation as one of the driving forces of change in the European workplace. The growing amount of data, its use in various industries and positions, the development of work on artificial intelligence and its potentially disruptive nature for the labour market make data analysis skills increasingly important.

However, I have noticed an interesting paradox. While mathematical and analytical courses are often seen as challenging, the empirical data contradicts this perception. For instance, the average score of mathematics in the 2023 Polish high school final exams was 71%, slightly higher than the Polish language average of 66% (CKE 2023). This discrepancy between the perception of mathematics as a subject difficult to master and the actual performance of students may be attributed to a cognitive bias. In my experience as a social and humanities didactician, I noticed that students often exhibited resistance towards quantitative analysis as part of their projects or an in-depth examination of analytically driven texts.

Additionally, working with culture students has shown me the enormous potential that lies within young people: the desire to fight, debate and bring about change. My students are not indifferent to harm, they have a rich conceptual apparatus and an incredible motivation to work. Given the magnitude and significance of these phenomena at the intersection of technology and socio-cultural reality, I felt compelled to bridge these worlds. A pressing question guided my research: how to channel this palpable passion — often manifested in the form of lively discussions, myriad ideas and tangible actions inspired by the humanities — into areas seemingly beyond their immediate interest. Specifically, I wanted to instil the pursuit of agency as an integral outcome of humanities studies, transcending the conventional perception of cultural studies as advanced essay writing. With access to a group of passionate, change-oriented individuals and data, an effective tool for social change, my goal was to integrate these elements.

As a result of my research and discussions with experts (data activists), I understood that there is no simple transition between data literacy and data activism. These are, of course, separate issues: the first one, as I explain below, is more a set of (future) competencies, important to be built today among as many people as possible; the second is the occupation of people who already have (or are building) these competencies (or are expanding them), thanks to which they understand how data can become a tool for change. And this has become my goal – by creating a transparent and simple data literacy course for (stereotypical) humanists, to provide them with an additional tool in their work, which in many cases is associated with being an activist. Of course, I do not claim that every cultural researcher or student who learns the basics principles of data collection and processing will become a data activist.

However, it is hard to become a data activist without understanding the tool you will be using. The aim of this short text is to look at the definitions of data literacy and data activism and to try to come to a consensus. This is also an opportunity to look at existing ways of teaching data literacy, including the experiences and knowledge of data activists, thanks to which I have been able to shed light on how people who practise data activism define their activity, but also to get to know their motivations, tools used, inspirations and ideas for running activist projects.

Why Data Literacy?

Data Literacy remains one of the most vital skills in modern societies, providing the ability not only to understand the nature of data, but also to use it for one’s own purposes. This key competency does not imply familiarity with complex analytical tools, but rather focuses on a critical approach to the process of data collection, analysis, and use. This way, a data literate person becomes not only a conscious data user of data but also a better citizen, employee, or member of the local community.

Data Literacy has different meanings in different settings. In a commercial setting, it is strongly tied to the skills of employees and the application of these skills in professional tasks. In an educational setting, the focus resides on skills related to data comprehension, although narrative and analytical aspects are significant.

From the perspective of shaping public policies, building civil society, or supporting local initiatives, data literacy is not only an important element in the process of grassroots change, but also a fundamental competency in the contemporary era of data ubiquity.

Catherine D’Ignazio and Rahul Bhargava (2015) define data literacy through the prism of four skills:

- Data reading, which involves understanding what data are and how they are created, what they mean, and what their limitations are;

- Working with data, which involves collecting, cleaning and managing data;

- Data analysis, which involves filtering, sorting, aggregating, comparing, and performing various operations on data;

- Conducting a discussion with data, that is, building an analytically supported story, taking into account the knowledge and habits of the audience group.

The researchers also note that data literacy differs slightly from so-called ‘big data literacy’, which additionally means understanding how data can be passively collected, understanding algorithmic pattern search on large datasets, and considering the ethical implications of using such data in decision-making processes that affect both individuals and entire societies.

Of course, data literacy is defined from many other perspectives, taking into account not only the above typology of skills but also focusing on both so-called hard skills (e.g., knowledge of data analysis tools) and soft skills (related to communication). The latter is highlighted by Jordan Morrow in his book “Be Data Literate” (2021), where he focuses on the so-called “3 Cs of data literacy”: curiosity, creativity and critical thinking.

These attributes are not only indicative of data literate individuals, but are also cited as fundamental competencies in a world characterised by data proliferation, the advancement of artificial intelligence, and the consequent labour market evolution (Marr 2022). Other noted soft skills include: collaboration, adaptability and emotional intelligence, t highlighting the human element within the sphere of future work.

One of the emerging paradigms in the data literacy discourse is the evolution of this notion towards ‘literacy in the age of data’. At the heart of this perspective is the recognition that data literacy is not an isolated skill but rather a mix of various forms of literacies, such as media, digital, computational, statistical, scientific, and information literacy. Rather than seeing data literacy as a mere subset or subtype of these literacies, the shift towards ‘literacy in the age of data’ means understanding that literacy as a whole must be adaptive. It must be equipped to deal with the rapidly changing digital landscape (the emergence of new Language Learning Models like ChatGPT is a good example). It should also be conceptualised as an ongoing process rather than a binary state of being literate or illiterate.

While this notion inherently involves understanding data, it also emphasises the applicability of such data in driving change within local communities. In this paradigm, where data literacy is visualised as part of a broader continuum in which different forms of literacy intersect and influence each other, being ‘data literate’ approximates the concept of data activism. The line between these two terms is becoming increasingly blurry (Bhargava et al. 2015).

However, the fundamental distinction lies in the nature and depth of engagement with data. In the ‘literacy in the age of data’ framework, individuals are positioned as participants in the information ecosystem—either as recipients or producers of information. Here, data can function as a tool to counter or challenge entrenched power structures. On the other hand, data activism is more concerned with the technical use of data and the modality in which these activist efforts are orchestrated. Through the lens of ‘literacy in the age of data’, we observe the information ecosystem holistically, recognising a spectrum of data comprehension levels among its actors. Learning to navigate this space can help achieve personal objectives or those of a particular community. Conversely, data activism can be seen as a niche within the wider field of data literacy, underpinned by a defined set of values and a specific social, political, or cultural issue. The efforts of data activists can be encapsulated in structured projects, actions or movements that revolve around this particular cause.

For the sake of clarity, what is data literacy? For the purposes of this text, I will adopt the definition proposed by the Gartner company, which defines data literacy as the ability to read, write and communicate data in context, including an understanding of data sources and constructs, the analytical methods and techniques applied, and the ability to describe the use case, application and resulting value (Panetta 2021). An important assumption of this definition is that data literacy does not have to mean so-called ‘technical literacy’, i.e. knowledge of advanced tools for collecting, processing and visualising data, but focuses on the process of collecting data and subjecting it to critical analysis. It is therefore not about being able to use Python to download data from Twitter, but rather about understanding what these data are, how they can be obtained, what their limitations are, and what can and cannot be said based on them (Brown 2021).

What is data activism?

There are various ways to define data activism. According to researchers Stefania Milan and Lonneke van der Velden, data activism encompasses a range of socio-technical practices that emerge at the margins of contemporary activism ecologies and focus on challenging datafication and its socio-political consequences. Data activism includes two distinct approaches to grassroots data politics: affirmative engagement with data and resistance to mass data collection. While these are often seen as contrasting, both address the fundamental paradigm shift brought about by datafication (Milan and van der Velden 2016, p. 61).

Milan and van der Velden emphasise the role of data and technology in defining what data activists do. They argue that data activism is deeply rooted in and shaped by data and software, both in terms of its availability and its use. Data activism can be seen as a form of socio-political mobilisation that brings together people, information and technology for actions that may vary be of varying degrees of contentiousness and that explicitly address, confront or engage with datafication. This mobilisation includes discrete events such as individual and collective acts of data appropriation, dissent, subversion and resistance to data collection, as well as the overall process of raising popular concern about datafication, signalling a fundamental shift in perspective and attitude within civil society (ibidem, pp. 61–62).

The constraints mentioned by Milan and van der Velden, data and software, leave room for interpretation. For example, can someone working with small data be considered a data activist, or does data activism only apply to those working with big data? Is hacking a government website a form of data activism? Dariusz Jemielniak and Aleksandra Przegalińska offer an answer to the latter question, pointing to hacktivism as a collaborative way of using technology for social change. They describe hacktivism as combining programming skills with critical reflection to work towards social change. However, they also note that hacktivism can be misused for malicious activism that undermines internet security. While data is present in hacktivism, it is not the primary focus; instead, the emphasis is on using technology for political or social causes (Jemielniak, Przegalińska, 2020, p. 86).

Despite the diversity of definitions of data activism, the common thread in all definitions is the idea of challenging power. DATACTIVE, a project led by Stefania Milan and Lonneke van der Velden, characterises data activism as a broad range of socio-technical practices critical of mass data collection. It involves both reactive data activism, in which individuals and groups resist threats to civil and human rights posed by corporate privacy invasions and state surveillance through technical solutions, and proactive data activism, in which people use big data for civic engagement, advocacy and campaigning (DATACTIVE, 2023).

Data activism is closely linked to civic engagement and does not necessarily require specific technical skills. It emerges from grassroots activism and evolves into a diffuse form involving ordinary users. Data activism occurs at the intersection of the social and technological dimensions of human action and aims to resist mass data collection or to actively use available data for social change (Gutiérrez, 2018). In the context of computer science, data activism may involve the use, mobilisation or creation of datasets for social causes, as well as the development and deployment of technologies that counter mass data collection (Kazansky, 2010; 2015).

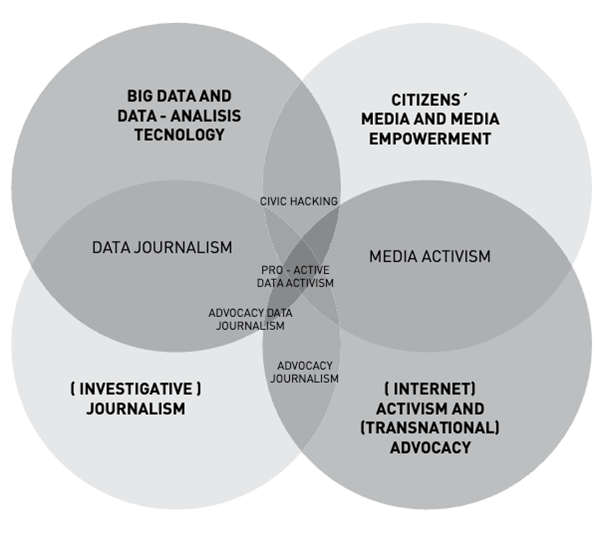

Overall, the classification of proactive and reactive forms of data activism proposed by Milan and van der Velden appears to be the broadest. Additionally, Stefania Milan, together with another researcher, Miren Gutiérrez, offers a comprehensive overview of the place of proactive data activism in a range of different forms of activism at the intersection of data, technology, journalism, media and advocacy. The diagram below illustrates these intersections.

So what do I mean when I talk about data activism? I am going to break this definition down into its component parts.

First, working with data. From my perspective, this encompasses any work with data, regardless of its volume or origin, and regardless of the skill level of the individuals handling it. This could range from highly trained data scientists to individuals with basic statistical skills performing simple data operations. One of the examples I have analysed (Atlas of Hate, described in the next section) illustrates that analysis is not a necessary component of a data activism project, but rather, that it can be about continuous, meticulous data collection and public disclosure.

Second, activism. This, of course, refers to social and political activism, the kind of activism that rallies people around an issue and seeks to bring about specific change and challenge power. In the book ‘Resist! How to be an activist in the age of defiance’, Michael Segalov outlines eight stages of activist work:

1) kicking down the door (an approach focused more on conflict than amicable change),

2) organising (the power of community and all the background to activist action, from meetings to logistics to discussions and reflection on the subject issue),

3) making noise about your cause (through media, including social media, public events, generating publicity),

4) shaping the future (a speculative but also partly opportunistic approach in which, using the media and the power of your movement, you give the movement an identity, a brand, that helps reinforce the message),

5) taking to the streets (including using the visual identification developed earlier),

6) knowing your rights (being prepared for any eventuality),

7) making a splash (through various actions, performances and activities that may, but do not have to, be controversial, thus attracting attention), and finally

8) preparing for the long haul (activist projects tend toy last for a long time, so one needs to must prepare for this, also to avoid burnout) (Segalov 2018).

From a data activism perspective, all of these elements can come into play, with data being the obvious tool for the battle. Referring to the Milan and Gutiérrez’s diagram that I described earlier, there’s a chance that some activist actions will take the form of (data) journalism or media activism, although of course they will differ in the methods used, the resources available, the goal or the motivation. The question of whether one can be an activist and get paid for their work remains open; this issue was strongly emphasised in my conversations with experts.

Therefore, by combining these two elements (data and activism) I will understand data activism as a social practice that uses data in any form to bring about specific social change in the name of certain values and principles and to challenge power. This action can touch on technological issues (surveillance via technology, opaque use of data by Big Tech), as well as other issues, although it usually leverages technology throughout the process. Its goal can be not only to raise public awareness of an issue through data, but also to lobby for specific change, to expose and highlight opaque processes and phenomena, inspired and led by companies and corporations, but also by governments and organisations.

What data activism projects exist?

While working on the project, I collected and analysed over forty different ideas for running data activism projects. The full list can be found here.

One of the highlighted projects is called Atlas of Hate (Atlas of Hate, 2023). This is a map of discriminatory local government resolutions (against “LGBT ideology”, “Regional Charters of Family Rights” etc). The map is based on a spreadsheet that is constantly updated (as of August 2023) to keep track of changes in these resolutions. Aside from the significant effort that went into data collection, the authors took care to label the data accurately, provide references, and create a database of all related information that can help interpret the dataset itself. The public reception of this project, together with Bart Staszewski’s photographic project (Jakubowska 2021), has been spectacular. According to the project’s creators, more than half of the homophobic resolutions were repealed as a result of its presence. This project is interesting mainly because it is based on a relatively small data set (small data), and its collection was a laborious process, as no method was found to automate it. Every resolution, every local government decision had to be verified. Of course, the scale of the project facilitated manual data collection, but it also sheds interesting light on the range of skills needed to carry out similar projects: among the technical skills, it is worth mentioning the ability to adeptly use Google Sheets and Google Maps. However, the most crucial skill appears to be the painstaking, difficult work of collecting data, contextualising it and the basic skills associated with comparing this data with others, e.g., the amount of EU subsidies withdrawn (as a consequence of adopting the document) or the termination of agreements between partner cities.

The second project is the Global Detention Project (2023), which tracks instances of people detained globally “for reasons related to their non-citizen status”. “Every day, tens of thousands of men, women and children are detained around the world for reasons related to their immigration status: asylum seekers, undocumented migrants, refugees, trafficking victims, torture survivors, stateless persons and others. The GDP relentlessly pursues information about where they are detained and how they are treated to ensure that their human rights are respected”, the website states. This project is different from the first in many ways: it is different in scale, the resources used, the amount of data collected, the number of communities potentially affected by its success, and more. Ad you navigate through the website, you will come across an interactive map showing ‘detention centres an idea of data use similar to that of the Atlas of Hate, but it also provides in-depth analysis at a country level and offers inquisitive readers detailed reports with contacts and specific recommendations.

Limitations of data activism

Although the actions of data activists bring obvious benefits and make significant changes, not every data activism action must be effective, nor can every action be perceived as appropriate, desirable or conscientious. When considering the actions of data activists, it’s necessary to consider not only the motivations behind their projects, but also the skills they use to accomplish them. For instance, in one of Professor Jonathan Cinnamon’s research projects, where he analysed activists’ reports and discussed their effectiveness, it was found that organisations whose activities are controlled within a data activism project could undermine their validity through poor methodology or a non-scientific approach. “There’s an idea that data can speak for itself,” Cinnamon said. “This idea can be a bit dangerous at the grassroots level because the city will simply contest the quality of the data. The findings of my research demonstrate that relying on data to narrate your story and political goal is sometimes a bit limited” (Cinnamon 2020).

So what are the of data activism projects and what should we be aware of? First of all, not all data is equally accessible, not all data can be downloaded in a way that is readable by the tools used (it may, for example, be in PDF format), some data may simply be unavailable. With this in mind, we should not only strive to open up as much data generated by public (and private, although this may be more problematic) institutions as possible, but also to improve the analytical skills of people working on data activism projects. With a better understanding of what data is and the limitations of analysing it, it will be easier to avoid potential errors, overinterpretation, or drawing conclusions based on insufficient or poor quality data.

Another limitation is the quality of the data. Activists should ask themselves: is the data I have complete? Who collected it and for what purpose? Can I identify any inconsistencies or potential biases in it? These questions can be reduced to a ‘data metric’ or, as suggested by T. Gebru et al. (2018), ‘datasheets for datasets’. The researchers suggest answering a list of questions related to the data collection process, so that subsequent users understand the context in which it was collected and the original purpose of its use.

Another issue is knowledge of tools and programming languages, but also understanding of technical infrastructure. Based on my analysis, data activism projects include technically trained people, but the question is whether their skills (and the amount of work they do) are adequate for the nature and complexity of the activist project. Put simply, not every data activist needs to know Python, not every data activism project requires this skill, but its absence can be a serious limitation on the quality of the project and its effectiveness. Another issue, of course, is the availability of resources: do we have enough people with the right skills? Can we afford to pay them for their work? How to solve these issues in smaller groups?

At the intersection of skills, resources and access to data, there are issues related to embedding data activism projects in a broader context. This involves an approach to your project that critically seeks to place it in a wide network of connections and relations that can enhance its effectiveness. It is also important for activists to reflect on their own positioning, the privileges they hold and how their situation, motivations, access to resources or even beliefs can influence their perception of the effectiveness of their actions, as opposed to what their actions actually achieve. I mean, considering the perspective of people who do not have access to the internet or technology (e.g., they do not have a smartphone), and who are part of the community for which the project is being run. There is also the issue of respecting the privacy of the data collected, securing the data collected, and ensuring for the informed consent of the people whose data is being processed.

It is also worth avoiding a (data-)solutionist perspective where the action we perform is the right (or only right) way to achieve a goal. Understanding complicated processes, phenomena and cultural nuances may not be possible through data analysis alone, and may require a deeper commitment that goes well beyond the scope of a data activism project. Its success is the result not only of thorough work on a data set, but also of deep understanding, interpretation and proper communication. Projects that resonate with the public can challenge governments or corporations, which can lead to resistance or chilling actions. An example of such good communication of the problem is the Atlas of Hate project, which, along with Bart Staszewski’s photographic project, not only drew attention to the problematic nature of local government actions but also gained considerable publicity. Its effect was not only that most municipalities withdrew their from controversial resolutions but also the threat of withdrawal of or actual withdrawal of European Union funding. In my opinion, it is important to maintain these projects, as designed, for a long time, precisely because of the resistance that activists may experience. Resistance that requires persistence, resilience and community support.

Conclusions: Data Activism and Democracy

Data Activism projects are intertwined with democratic processes in many ways. It involves collecting and analysing data to expose hidden information or shed light on issues that might otherwise remain hidden. By promoting transparency, openness and accountability, data activism projects help to foster democracy, but also ensure that citizens have unrestricted access to all the information that can help them make a decision during elections or simply advocate for change in their local communities. By analysing data related to government spending, policy decisions, environmental impact or human rights abuses, data activists can provide evidence to demand greater accountability from those in power. We need to remember, though, that the potential impact of data activism is heavily influenced by the prevailing political and social climate. In societies where democratic institutions are weak or undermined, data-driven evidence might not be enough to bring about meaningful change or hold those in power accountable.

It is clear that data, when made available and easy to understand, can be a powerful tool in shaping democratic processes. The availability and usability of data enables citizens to participate more effectively in debates, policy discussions and decision-making. What is more, having access to fact-checked data can also help combat disinformation and misinformation by providing verifiable data and evidence.

On the other hand, it is important to note that the mere act of collecting and analysing data does not necessarily lead to these outcomes. The data itself is value-neutral; it is how it is used and interpreted that can drive change. Data can be manipulated, misrepresented or selectively presented to promote particular viewpoints or interests, even within the context of data activism. Therefore, data activism projects need to be grounded in ethical and responsible data use principles, including honesty, integrity, and a commitment to truth.

Mimi Onuoha (2016) once pointed out that there are some datasets that do not exist, which means no public policy can be put in place. Not collecting data is also an emanation of power. Data activists can have a huge impact here by finding these blank spots and filling them with data, carefully. It is important to understand that while data can help shed light on some issues (such as violence against transgender people), it also poses a threat to people’s privacy and security. In a democracy, the privacy and protection of citizens’ data is paramount. Data activism can advocate for strong data protection laws and raise awareness about potential privacy violations by governments and corporations. However, it is worth noting that data activists themselves have a responsibility to handle and protect sensitive data responsibly, particularly when dealing with data about vulnerable or marginalised populations. It’s essential to recognise that data activism in itself is not a substitute for a well-functioning democracy. While it can enhance democratic processes, it must work in tandem with other democratic principles such as the rule of law, free press, independent judiciary and a vibrant civil society. An over-reliance on data and quantification can lead to ‘datafication’, a belief in the superiority of data-driven decision-making, which can sideline other valuable forms of knowledge and wisdom. We must remember that an emphasis on data can perpetuate inequalities, as those with the resources and skills to access, analyse and use data effectively are often the most privileged individuals or groups in society, including data activists.

[1] Humanity in Action Polska, https://humanityinaction.org/action_project/landecker-democracy-fellowship-from-data-literacy-to-data-activism/ (access: 26.11.2023).

Bibliography

- Atlas of Hate. (2023). Atlas of Hate. https://atlasnienawisci.pl/ (access: 11.07.2023).

- Bhargava, R., Deahl, E., Letouzé, E., Noonan, A., Sangokoya, D. & Shoup, N. (2015). Beyond Data Literacy: Reinventing Community Engagement and Empowerment in the Age of Data, DataTherapy.org. https://datatherapy.files.wordpress.com/2015/10/beyond-data-literacy- 2015.pdf (access: 9.08.2023).

- Brown, S. (Feb 9, 2021). How to build data literacy in your company, MIT Sloan. https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/how-to-build-data- literacy-your-company (access: 16.07.2023).

- Cinnamon, J. (2020). How powerful is data activism?, Toronto Metropolitan University. https://www.torontomu.ca/research/publications/newsletter/2020- 07/data-activism/ (access: 12.07.2023).

- (Jul 7, 2023). Wstępne informacje o wynikach egzaminu maturalnego przeprowadzonego w terminie głównym (w maju) 2023 r. cke.gov.pl. https://cke.gov.pl/images/_EGZAMIN_MATURALNY_OD_2015/Informacje_o_wynikach/2023/20230707%20Wstepne%20informacje%20EM23%20werFIN.pdf (access: 8.08.2023).

- (2023). The Politics of Data According to Civil Society, Datactive. https://data-activism.net/about/ (access: 16.07.2023).

- D’Ignazio, C., & Bhargava, R. (2015). Approaches to Building Big Data Literacy. In Bloomberg Data for Good Exchange. New York, NY, USA.

- Global Detention Project. (2023). https://www.globaldetentionproject.org/ (access: 11.07.2023)

- Gebru, T., Morgenstern, J., Vecchione, B., Wortman Vaughan, J., Wallach, H., Daumé III, H. & Crawford, K. (2018). Datasheets for Datasets, Communications of the ACM, Volume 64, Issue 12.

- Gutiérrez, M. (2018). Data Activism in Light of the Public Sphere. Krisis, Issue 1, 2018: Data Activism.

- Jakubowska, J. (Jan 4, 2021). Poland: No country for LGBT+ people? Interview with an LGBT activist Bart Staszewski // PODCAST, Euractiv.pl (access: 12.07.2023).

- Jemielniak, D. & Przegalińska, A. (2020). Collaborative Society. The MIT Press.

- Marr, B. (Aug 22, 2022). The Top 10 Most In-Demand Skills For The Next 10 Years, Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2022/08/22/the-top -10-most-in-demand-skills-for-the-next-10-years/ (access: 17.07.2023).

- Milan, S., van der Velden, L. (2016). The Alternative Epistemologies of Data Activism, Digital Culture & Society 2 (2).

- Milan, S. & Gutiérrez, M. (2015). Citizens’ Media Meet Big Data: The Emergence of Data Activism, Mediaciones, No. 14.

- Morrow, J. (2021) Be Data Literate: The Data Literacy Skills Everyone Needs to Succeed. KoganPage.

- Onuoha, M. (2016). The Library of Missing Datasets. https://mimionuoha.com/the-library-of-missing-datasets (access: 17.07.2023).

- Panetta, K. (Aug 26, 2021). A Data and Analytics Leader’s Guide to Data Literacy, Gartner. https://www.gartner.com/smarterwithgartner/a-data- and-analytics-leaders-guide-to-data-literacy (access: 17.07.2023).

- Segalov, M. (2018). Resist! How to be an activist in the age of defiance. Laurence King Publishing.